Thoughts about Shangri-la while quarantined at Shangri-la

Quarantined for 14 days Singapore’s Shangri-la (on Sentosa Island, Singapore), and Shangri-la being a luxury 5-star hotel on Sentosa Island off Singapore, I suppose it qualifies as a tropical paradise on earth. In the middle of a pandemic, I am grateful that it is the appointed location for my temporary incarceration and separation from the rest of the world here in comfort, fully paid for by the government … I only have to take my Covid-19 swab test and wait out my swab test results, meanwhile, try to make plans for the uncertain future that lies ahead.

Jacket cover from first edition of Lost Horizon the novel by James Huilton, that popularized the idea of Shangri-la Photo: Wikipedia, Fair use

And so during the 14 days here in my Shangri-la resort retreat, I turn my thoughts to the name Shangri-la, the name borrowed from the ancient tale of a earthly paradise discovered by plane survivors in a remote valley west of Tibet that was immortalized in the novel Tale of ‘Lost Horizon’. In that paradise setting was a lamasery (headed by a 200 year old Capuchin lama) that kept all the cultural treasures of the earth and where its society was opposed to violence and materialism. Set in the shadow of the loveliest mountain on earth and in the Himalayan “Land of Snows”, the story was made famous by Frank Capra’s 1937 moviie, considered a “tour de force” and a success, though criticized for being an overbudget and lavish production for 1937.

Movie poster Illustration by James Montgomery Flagg. “Copyrighted by Columbia Pictures Corp., New York, N. Y., 1937″. via Heritage Auctions. Now in the public domain

What sticks in my mind is Graham Greene’s criticism in the Spectator of the movie:

Nothing reveals men’s characters more than their Utopias … this Utopia closely resembles a film star’s luxurious estate on Beverley Hills: flirtatious pursuits through grape arbours, splashings and divings in blossomy pools under improbable waterfalls, and rich and enormous meals … something incurably American: a kind of aerated idealism (‘We have one simple rule, Kindness’) and for Greene, apparently, a film about Utopia is “very long” and “very dull”.

Greene, Graham (30 April 1937). “‘Lost Horizon’ at the Tivoli”. The Spectator. p. 21

Greene while criticizing the “aerated idealism” of Hollywood fantasy, unfortunately, did not explain what his ideal Shangri-la should look like. What should a current Shangri-la look like in our popular imagination in 2021 today? Would we care about gathering cultural treasures and wisdom of the world or more about off-the-grid now that we face a war against invisible viruses and human extinction, instead of staring down the barrel of WWII soldiers or nuclear arsenal?

There are no snowy peaks here at Rasa Sentosa Shangri-la of course, this being sunny and the very flat granite island of Singapore. And it is pretty much raining elephants, rather than cats and dogs with the tropical downpours daily. It has been virtually impossible to step out onto a flooded balcony.

And so even though I am really very very grateful to be ensconced in five-star hotel, my Shangri-la is really no Shangri-la Utopia. It is really a “very long” two weeks of anxious trepidation awaiting Covid test results, unable to leave a room, nor permitted to explore the facilities and lovely grounds of the hotel, not even when my swab tests return negative and I am pronounced free of Covid. I am impatient to pursue more pragmatic tasks and embark on urgent duties and being reunited safely with my family. This reminds me of the trip when I fell ill with a fever while heavily pregnant with my first child, and had spent most of my days in feverish delirium on my way to a wedding while having to recuperate in bed between two gorgeous chateaux in Loire and then Burgundy. What do all the chateaux in the world mean, if you have not your health. Without health, you have no wealth. During a pandemic, one’s mind, and if one can afford it, one escapes to a Shangri-la of some sort.

To be fair, the prologue to Lost Horizon explains its Shangri-la context:

“In these days of wars and rumors of wars — haven’t you ever dreamed of a place where there was peace and security, where living was not a struggle but a lasting delight? . . .”

And defined thus, Shangri-la still has relevance and attraction for us in 2020~2021 if you swap out hot wars for the global health crisis. Tales of Utopias of Shangri-la are manufactured often during times of chaos and turmoil, and always have great appeal in such times. The Lost Horizon was written by James Hilton in 1933 during the pessimistic mood of the 1930s, when Western civilization seemed bent on a path to self-destruction – and when, as Carl Jung put it, ‘the smell of burning was in the air’ – But now even more so during a pandemic, everyone longs to escape to some villa if not lamasery, in an idyllic valley faraway from decay and corruption of the flesh, just like in Shangrila where its inhabitants escaped disease and seemed to be nearly immortal and to age slowly… so long as they didn’t leave Shangri-la.

Likely based on the lost kingdom that Jesuit missionary Father Antonio de Andrade went in search of, Shangri-la may have had its origin in an ancient tale told by a visitor to the Mughal emperor’s court of Akbar, of treasure and stories of a Tibetan kingdom at Lake Manasarovar, which was then recorded in an essay by a very old visiting missionary in a 16th century manuscript complete with an accompanying sketched map, and notes that said, “here it is said Christians live”.

Father Andrade’s accounts of Tibet are believed to have been drawn heavily upon by Hilton for his Lost Horizon novel. Father Andrade made an arduous journey in 1524 arriving in Tibet marking the first known encounter for Europeans with Tibet. Received well in Tibetan capital city Tsaparang by the sovereign of the Western Tibetan kingdom of Guge, he made a second trip in 1625 and succeeded in building a mission church. Father Andrade’s two extensive accounts of Tibet, written in 1624 and 1626, were published in the Portuguese original in Lisbon in 1626, with many European translations, and a 2017 English translation as well.

At the time, the Western world began to converge or encroach upon the East. So it was at a time when the world order as they knew it must seemed to have been shifting. At the time, the Muslim dynasty of Turkic-Mongol origin had ruled most of northern India in a glorious Golden Age from the early 16th to the mid-18th century. The Mughal dynasty was notable for its more than two centuries of effective rule over much of India; for the administrative ability of its seven generations of talented rulers. When compared to today’s world affairs, the Mughals were incredibly successful at integrating Hindus and Muslims into a united Indian state. Akbar’s response to the arrivals of Westerners was to gather scholars of all races around him, hoping to find the common basis of all religions, in order to remove the sources of religious conflict for the good of humankind. His court congregated Hindus, Yogis and Sadhus from all corners of his empire, as well as visiting Christian monks and pilgrims from western lands. Attributed to Akbar are these words:

It now becomes clear … that it cannot be right to assert the truth of one faith above any other … In this way we may perhaps again open the door whose key has been lost.

Akbar the Great (1556-1605) is widely considered the greatest of the Great Mughal rulers of that time and his court was the conduit of knowledge about Tibet to the West. When Padre Andrade first arrived in Agra, Akbar’s son Jahangir (1605-1627) was the Mogul Emperor. Akbar was a Muslim, but allowed the practice of beliefs from other religions and encouraged the open expression of religious opinions.

After spending several years in Agra, Padre António de Andrade became the Superior of the Mogul Mission and governed the Jesuit missions in the area north of Agra that extended into and over the mountain ranges and included Tibet. Jahangir was followed on the throne by his son Khurran(a.k.a. Shah Jahan) who ordered the Taj Mahal to be built.

Scholars often note that the practice of religious tolerance is a common thread that saw many empires (from the Roman empire, to the Tang dynasty) with wise leadership, while allowing them to flourish to greatness, while on the whole seeing reduction of conflicts and having true peace. Tolerance for diversity will only help integrate a society divided, when there develops a respect and an appreciation for initiative and creativity and new skills or qualities brought by an immigrant minority or ethnic ingroup and/or if ideologies and beliefs about a just world and meritocracy promoted.

And so, what would a truly “great” Utopian Shangri-la look like?

It would be a sanctuary from the troubles of the day. The Shangri-la of Hilton’s Lost Horizon was an escape from the chaos of the Great Depression and the political crisis that culminated in the Second World War.

A second candidate for the Lost Horizon’s Shangri-la was Shambala. A Tibetan Buddhist legend of a Utopian paradise and refuge where people of all religions and backgrounds live together in peace and harmony, and war and sorrow were unknown. This Shambala paradise was found in a land behind the Himalayas, ruled by a gracious King Sucandra, who was the first to learning the Kalachakra doctrine from Buddha Sakyamuni himself. Where is Shambala? The land of Shambala “lies in a valley. It is only approachable through a ring of snow peaks like the petals of a lotus … At the centre is a nine-story crystal mountain which stands over a sacred lake, and a palace adorned with lapis, coral, gems and pearls.” Shambala is a kingdom where humanity’s wisdom is spared from the destructions and corruptions of time and history, ready to save the world in its hour of need. The legend comes complete with an endtimes apocalyptic prophecy of a final great battle. Hmmm, a place from which, when war and evil engulf the rest of the world, a leader, a saviour will emerge to defeat the forces of chaos and usher in a new age of peace and happiness. Where have we heard that before?

In light of what the chaos we have witnessed during 2020, we have witnessed a world that is impacted by increasing religious and racial intolerance and violence and property damage from both those incensed by racial inequality and injustice on the left, and burgeoning violence and belligerence from the right and extreme viewpoints and willingness to inflict harm and death upon minority people and groups and their sacred spaces.

Right about now, a Utopian Shangri-la looks like:

– a relatively secluded and unpopulated (read “socially distanced” from others) place

– that is free of disease and death I.e. Covid-free, free from violence, conflict and hate speech and hate crimes, and

– that is peopled by inhabitants going about life in an orderly and in my own opinion… unpsychotic way.

Not so different from the Shangri-las, Shambalas, Sumerus (Mt Meru, cosmic abode of the gods) of old. Several candidates for Shangri-la include Ladakh in the Karakorum; Zhongdian’s Shangri-la in Yunnan; the vicinity of Tibetan Mt Kailash; the Hunza Valley in Northern Pakistan

Many will be seeking today escape from racial and religious conflicts and tensions and from horrific pandemic crisis that most of the world is currently yet to overcome.

In times past during the eleventh century, during the Turkish attacks on Greece, monks occupied and hid in the caverns of Meteora … the famed monasteries were not built until the fourteenth century. The first people documented to inhabit Meteora after the Neolithic Era were an ascetic group of hermit monks who, in the ninth century AD, moved up to the ancient pinnacles. They lived in hollows and fissures in the rock towers, some as high as 1800 ft (550m) above the plain. This great height, combined with the sheerness of the cliff walls, kept away all but the most determined visitors.

In 1344, Athanasios Koinovitis from Mount Athos brought a group of followers to Meteora. From 1356 to 1372, he founded the great Meteoron monastery on the Broad Rock, which was perfect for the monks; they were safe from political upheaval and had complete control of the entry to the monastery. The only means of reaching it was by climbing a long ladder, which was drawn up whenever the monks felt threatened. By the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, a rudimentary monastic state had formed called the Skete of Stagoi and by the end of the twelfth century, an ascetic community had flocked to Meteora.

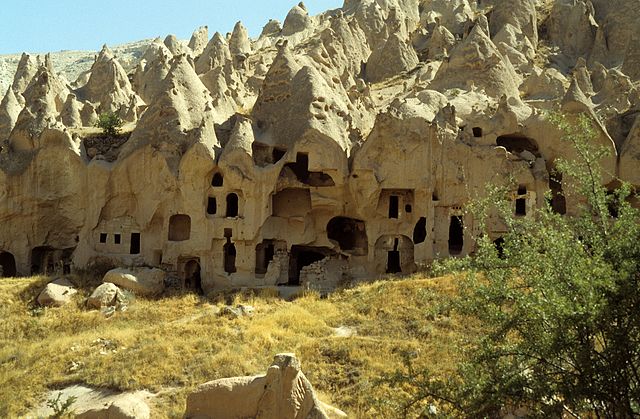

Similarly with Cappadocia, beginning in the first centuries AD, starting with hermits who retreated into the seclusion of the tuff landscape settling in caves that already existed or dug their own residences in the cliffs. Since they were seeking solitude rather than protection from enemies, they largely made their homes above ground level. In the fourth century AD, ever larger groups of Christians followed them over the next few centuries, settling in Cappadocia and building cloistered communities, but from the fourth century, intensive construction of rock-cut buildings below and aboe ground were built for security and defensive functions to shelter from the invasions of the Isaurians invaded, in the fifth century the Huns, and finally in the sixth century the Sassanid Persians; and in 605 for refuge from the the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 and from 642, the invasions by the Arabs.

Photo credit: Klaus-Peter Simon, CC BY 3.0

Photo credit: Klaus-Peter Simon, CC BY 3.0

In the first centuries AD, starting with hermits who retreated into the seclusion of the tuff landscape from the Christian community at Caesarea. They either settled in caves that already existed or dug their own residences in the cliffs. Since they were seeking solitude rather than protection from enemies, they largely made their homes above ground level. Ever larger groups of Christians followed them over the next few centuries, settling in Cappadocia and building cloistered communities, which meant that they needed ever more and ever larger residential and religious spaces. Meanwhile, in the fourth century, the Isaurians invaded, in the fifth century the Huns, and finally in the sixth century the Sassanid Persians; in 605 the city of Caesarea was conquered during the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628. These incursions sparked the intensive construction of rock-cut buildings below and above ground, including whole cities. The design of these structures was principally shaped by security and defensive concerns. The Arabs began to invade the region from 642 and these concerns grew increasingly significant, with the result that Christian communities continued to live in the region for three centuries, secure from raids.

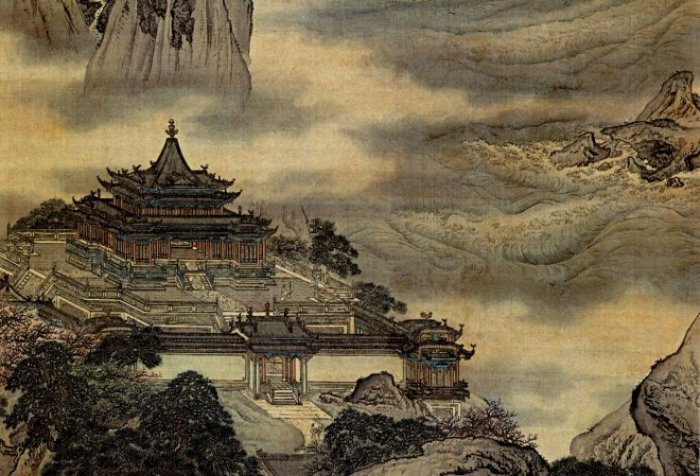

All these ancient models of paradise notwithstanding, judging by how Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner have already left for their own slice of paradise on the very exclusive Indian Creek Island in Miami, with only 29 residences on Indian Creek Island peaks, today’s Shangri=las actually look more like Rasa Sentosa Shangri-la. Since ancient times, in the Ryukyu kingdom of Japan, this paradise was called Nirai-Kanai, a paradise island beyond the seas, where the gods came from, and from whence originated great blessings and good things. The Chinese version was Mt. Penglai an eastern paradise island of eight immortals who lived on the peaks of the mountain that had palaces of gold.

To sum up popular thought, when signs of a troubled and chaotic world order at one’s doorstep, concepts of paradise retreats fall into these categories:

- A secluded mountain valley like Lake Manasarova’s Tibetan lamasery where immortals may be found

- A cosmic mountain peak like Shambala or Shangri-la or Sumeru thought to be Mt Kailash

- A mandala paradise either allegorical or physical on earth where you can align yourself to connect with the divine or spiritual cosmic universe, like Angkor Wat an actualized physical city constructed and based on the mandala model of Mt Meru

- A paradise island where immortals live like Nirai-kanai or Mt. Penglai

- Caverns and rocky sanctuaries and monastery retreats of Meteora and Cappadocia that are also influencing interior design

Just an observation, many of these Utopias also fit the bill for the Doomsday Cult Compound. Cults grow and their membership thrive on the very same conditions that lead people to retreat from a chaotic world. Rocco Leo leader of the notorious Agape Ministries and who had fled to Fiji in 2010 had warned followers of a 2010 apocalypse, claiming that everyone on Earth would be implanted with microchips and those who refused would be killed by the government. Leo promised to save cult members by taking them a place called ‘The Island’ in the South Pacific if they handed over their life savings. His 15.3 hectare residence and HQ called the Kuipto Colony Retreat, located one hour south of Adelaide was described as ‘overlooking lake-like dams and being privately located in a beautiful hills setting between Meadows and Willunga. According to the Architizer, doomday cult leaders

sought sites that were neither here nor there: an abandoned hotel, an unused ranch, a barren desert, or a cheap tract of land in a faraway country the American cult denies past use and creates a utopia in or on their chosen site. Like the walls of the Watchtower or Rajneeshpuram’s city-within-a-city, these compounds negotiate and politicize their relationship to the outside world. They are massive in scale and their totalizing vision reveals an earnest anxiety about the future. Compounds demarcate space so that time can move differently (or not exist at all) within the designated area. Particularly in the case of doomsday cults, they create an unshakable urgency that reveals a deep fear of being in the present. The walls of the compound manage small worlds—taking their followers out of the real and placing them within an imagined other.

Katherine Wisniewski, Cult-itecture: The Compounds Of Intentional Communities

6. My own idyllic Shangri-la favourite however, resembles more the Ewok treehouse community retreat, such as that found in Chateaux dans les Arbres, Surrey’s fairytale village or Toledo’s Treetop community Yes, a treehouse is the very thing for me. Make that a fairytale mini-chateau-treehouse, and my life would be complete!

Tell us in your comments below which of the six Shangri-las would your idyllic Shangri-la place look like?

References:

- Gary Arnold, ‘Found Horizon’, Washington Post, 1986

- Angkor Wat as a mandala Dokras, Uday and Dokras, Srishti, 2020/07/09

- Lost Horizon. 1937 Frank Capra film

- Adelaide doomsday cult compound up for sale billed as a ‘unique and flexible property’ after leader who fled to Fiji is forced to sell assets, Daily Mail, 30 July 2014